Rascals case in brief

In the beginning, in 1989, more than 90 children at the Little Rascals Day Care Center in Edenton, North Carolina, accused a total of 20 adults with 429 instances of sexual abuse over a three-year period. It may have all begun with one parent’s complaint about punishment given her child.

Among the alleged perpetrators: the sheriff and mayor. But prosecutors would charge only Robin Byrum, Darlene Harris, Elizabeth “Betsy” Kelly, Robert “Bob” Kelly, Willard Scott Privott, Shelley Stone and Dawn Wilson – the Edenton 7.

Along with sodomy and beatings, allegations included a baby killed with a handgun, a child being hung upside down from a tree and being set on fire and countless other fantastic incidents involving spaceships, hot air balloons, pirate ships and trained sharks.

By the time prosecutors dropped the last charges in 1997, Little Rascals had become North Carolina’s longest and most costly criminal trial. Prosecutors kept defendants jailed in hopes at least one would turn against their supposed co-conspirators. Remarkably, none did. Another shameful record: Five defendants had to wait longer to face their accusers in court than anyone else in North Carolina history.

Between 1991 and 1997, Ofra Bikel produced three extraordinary episodes on the Little Rascals case for the PBS series “Frontline.” Although “Innocence Lost” did not deter prosecutors, it exposed their tactics and fostered nationwide skepticism and dismay.

With each passing year, the absurdity of the Little Rascals charges has become more obvious. But no admission of error has ever come from prosecutors, police, interviewers or parents. This site is devoted to the issues raised by this case.

On Facebook

Click for earlier Facebook posts archived on this site

Click to go to

Today’s random selection from the Little Rascals Day Care archives….

Click for earlier Facebook posts archived on this site

Click to go to

Today’s random selection from the Little Rascals Day Care archives….

Day-care panic rooted in more than sex-role changes

georgecaseblog.wordpress.com

George Case

Sept. 23, 2016

“We Believe the Children” offers a clear explanation of how a then-novel crusade for child welfare and a murk of neo-Freudian psychological theory together drove officials to find suppressed trauma where none existed, and [Richard] Beck also cites the popular nonfiction books Sybil (1973) and Michelle Remembers (1980) for their role in spreading acceptance of Multiple Personality Disorder and Satanic Ritual Abuse as authentic phenomena.

“He further argues that the day care scandals represented a conservative backlash on behalf of traditional family structures, in which fathers worked while mothers stayed at home to raise children, over the newer model of two busy parents dropping their kids off with professionals. In this reading, the contemporaneous wave of incest survivor memoirs and self-publicizing MPD victims likewise reinforced the traditionalist ideal of helpless females unable to cope in a modern society that gave women too much sexual and career freedom.

“Maybe. Yet Beck only devotes a paragraph or two to the burgeoning pop-culture fascination with the occult which preceded the Satanic panic, and it’s worth pointing out that, despite hit films like The Godfather and Scarface, no one in the 1980s was accused of recruiting children into a mobster underworld, and despite turmoil in the Middle East, day cares were not suspected of being fronts for Islamic terrorists.

“Rather, the emphasis on perversion, ritual killing, and cultism which characterized the scare drew on obvious sources in the mass entertainment of the mid-1960s onward. As I’ve written in my book Here’s To My Sweet Satan: How the Occult Haunted Music, Movies, and Pop Culture, 1966-1980,

For a culture accustomed to the bloody rampages of Charles Manson, the shameless perversities of Anton LaVey, and the no-holds-barred gross-outs of The Exorcist, such combinations of cruelty, vulgarity, and the occult [in the McMartin charges] were no longer surprising.…For a long time the public had been bombarded with messages of what Satan and Satanists were like, of the words, images, and symbols associated with devil worship, and especially of how children were Satan’s favorite victims. It had all finally proved too much for some people.

“I believe it’s this influence that fostered the climate for McMartin and other travesties, at least as much as any right-wing fantasies about dutiful moms and dangerous outsiders….”

– From “Children of the Grave” by Canaadian author and blogger George Case (Sept. 23)

An earlier challenge to Beck’s emphasis on conservative backlash points a finger at feminism.

![]()

Another child-witness, now grown, spills the beans

Sept. 8, 2015

“Jennifer (a pseudonym) reached out to me after seeing an interview I gave about the McMartin Preschool trial…. She said she had been involved in a similar case as a child and that her experiences with the police, the judicial system, and a series of therapists mirrored those of the McMartin children. Now an adult with a career and family of her own, she agreed to speak with me about her experiences during the trial and in the decades since….

“Jennifer’s experiences illustrate the consequences of the misguided ‘belief’ in children that so many therapists, parents, and cops professed during the 1980s….”

– From “Moral Panic and the Myth of Recovered Memory” by Richard Beck at Literary Hub (Aug. 18)

Although Beck presents more as a historian than a journalist, his interview with Jennifer is a significant addition to the sparse roster of recanting (or not) child-witnesses. Not surprisingly, her account offers numerous parallels not only to McMartin but also to Little Rascals:

- “lots of phone conversations and meetings” among parents

- an interviewer with “anatomically correct dolls”

- her initial insistence that “nothing had happened”

- “a tour of the jail” arranged by the therapist to assure her that the supposed molester was safely behind bars

- her capitulation in the face of endless therapy sessions, leading her to “finally just start… making stuff up.”

- the eventual overturning of her day-care teacher’s conviction

Might Jennifer’s coming forward, however tentatively, lead the way to more recantations by child-witnesses?

‘A hard core of evil in the soul of humankind?’

Oct. 20, 2015

Oct. 20, 2015

“(Richard Beck’s “We Believe the Children”) addresses only the question of why those events unfolded in the particular way that they did, at one particular moment – not why this hydralike form of communal social hysteria can be stamped out in one place only to rear another ugly head elsewhere.

“Perhaps there is no answer to that question – or, at least, no answer we want to hear. Politics, social mores, human psychology, a rye-eating fungus: all these submit calmly to our investigations. But a hard core of evil in the soul of humankind? That might be the real witchcraft, one we dare not examine too closely.”

– From “Trial and Error: Three centuries of American witch hunts” by Ruth Franklin in Harper’s Magazine (Oct. 17)

Edenton’s history was no defense against panic

Jan. 28, 2013

Jan. 28, 2013

Manhattan Beach, California; Malden, Massachusetts; Christchurch, New Zealand; Maplewood, New Jersey; Sao Paulo, Brazil…. For more than a decade, unfounded allegations of day-care ritual abuse were breaking out all over the planet.

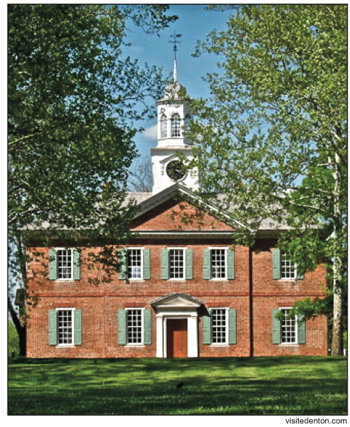

But for sheer cultural anomaly it’s hard to match the emergence of such a case in historic and pristine Edenton, North Carolina, not unreasonably billed as “the South’s Prettiest Small Town.”

Edenton had made lots of headlines before Little Rascals, but almost none since the 1700s.

Among the town’s prominent residents: Joseph Hewes, signer of the Declaration of Independence; Hugh Williamson, signer of the Constitution; James Iredell, George Washington’s youngest appointee to the U.S. Supreme Court.

Penelope Barker hosted the Edenton Tea Party to protest British taxes (that’s her waterfront house in the opening scene of “Innocence Lost”).

Harriet Jacobs, author of “Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl,” was a native.

You won’t find a Walmart in Edenton (population 5,000 and slowly shrinking), but its trove of civic treasures includes a 1925 moviehouse, a 1939 baseball park and a 1767 courthouse (above right), the state’s oldest.

So why Edenton of all places? How did this charming, 300-year-old hamlet happen to offer all the essential ingredients for a world-class ritual-abuse panic? I wish I knew (and I wish Edenton did too).

0 CommentsComment on Facebook